Better, Together

5-minute read

Better, Together

5-minute read

At first, Cheryl figured her partner Jerry was just recovering from major surgery. The U.S. Air Force Veteran lacked energy; he didn’t have much interest in eating. But then again, he’d just had open heart surgery.

And Jerry had reason to feel down. Cheryl and Jerry's dog died on the Fourth of July, and their other dog had organ failure. They had raised their dogs from puppies, so Cheryl figured Jerry was naturally upset about that as well.

Eventually, she realized it was more than that.

“He would sit in a chair in the living room and watch TV, and he would not want to eat a meal,” Cheryl remembers. “And he would not come to bed. I had to fight him to get him to take a shower. He seemed to have depression off the charts.”

**

When do you get more involved? When do you share more than maybe you’d otherwise be comfortable sharing about what your partner is going through? When do you reach out for help? And when do you put your foot down?

These are questions that Cheryl has navigated. “If you are in a relationship with somebody, you do need to act,” she says. “You do need to explore. You need to get involved as soon as you see signs that alarm you. The sooner the better. … And now I’m wiser — older and wiser — but it took a lot for me to get to the point where I am.”

**

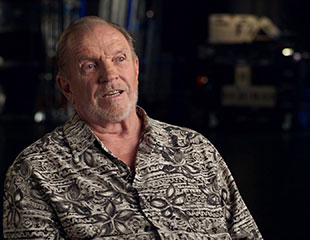

Jerry played the trumpet in the Air Force Band. He had excelled at music in high school, and a mentor had encouraged him to audition. He enlisted when he was 17, traveling across the United States and in countries beyond. He also played at a lot of funerals.

After leaving the service, Jerry started a family, went to school on the GI Bill, and began a career in sales. He met Cheryl in the 1980s, when he was going through a divorce.

Fast-forward to 2011. It was Cheryl who pushed Jerry to talk with a doctor about his declining health. She went with him to his appointment, writing out a list of questions about his symptoms. When it was revealed that Jerry needed heart surgery to replace a valve, she spoke with his surgeon about his heavy drinking.

“The surgeon … told me it was a very good thing that I shared with him Jerry’s drinking habits, because he would be displaying withdrawal symptoms, and they would not know that that’s what was wrong with him. And he could die just because they did not know that was what was going on,” Cheryl says.

About a month after the surgery, Jerry developed an excruciating case of shingles across the left side of his body. “Probably the worst pain I’ve ever had,” he says. “All I could do was sit in the chair, watch TV, and cry.”

To help him deal with the pain, his doctor changed his medication from Valium to Oxycodone. “That was lights out for me,” Jerry says. “But I decided it wasn’t going to work, or I [felt] it wasn’t working. But I’d wake up in the morning, I have to take my Oxycodone and wash it down with vodka. And then from then on, it’s sort of fuzzy.”

Somewhere along the way, Cheryl — realizing now that this was something other than depression — called Jerry’s children: “You’re going to lose your dad,” she told them, “if somebody doesn’t help me with the problems that I am seeing.” They eventually helped him get into a private facility to deal with his substance use.

“As much as I got involved in his medical care, I did not perceive that there was an issue with prescription medications,” Cheryl says. “I regret it immensely now, but I didn’t think of it. I didn’t check on medications. I had no idea that that was exacerbating the alcoholism.”

My advice to somebody in a close relationship with a person that is not behaving in a healthy manner, who is not communicating, who is hiding what they’re doing — [is] that may only be the tip of the iceberg.— Cheryl, Jerry's partner

For months, Jerry battled a tough cycle: he’d attend a substance use program, get out, and then immediately begin misusing substances again—not with the oxycodone, but with his drinking. This happened once, twice, and a third time. Finally, Cheryl set an ultimatum.

“I told him he was not welcome to come back until he had completed a program, No. 1, and No. 2, lived on his own and was able to maintain on his own a healthy lifestyle — and prove to me that he was committed to that,” Cheryl says. “And I stuck to my guns. But I also told him that as long as he continued to try, I would support him. I would come and see him. And I did.”

The conversation hit Jerry hard. Even now, his voice catches as he recounts her message: “Don’t come back until you’re well.” He called a friend and stayed with her. “I didn’t sleep,” he says. “I just had thoughts of suicide.”

A day later, he was taking the bus across town to gather some of his belongings, when the bus stopped right in front of the VA medical center. He looked over, saw the building, and said to himself: “I got to be in there.”

An hour later, Jerry was in the psychiatry ward and stayed for 21 days. Over those three weeks, counselors encouraged him to enroll in a VA substance use disorder program.

It would prove life-changing. The program was a 24/7 immersion that kept Jerry going to meetings and busy with chores, and it taught him about addiction and alcohol use disorder.

“I finally got to realize that it’s … a disease, and it had to be treated like that,” he says. Treating the symptoms wasn’t working. “You had to learn what was causing them … and how to cope with them, and … what triggered them.”

Jerry had been blaming himself, and the counseling taught him how to deal with that loss of feeling self-respect and self-worth. “You get past that and realize that it’s a disease and it’s treatable,” he says. “Treat the disease. Learn coping skills. Know when they’re going to happen or what triggers you. And trust your behavior accordingly. That was a tremendous help for me.”

**

The program included 90 days of inpatient treatment and then 90 more days of outpatient care. Jerry spent another two years living away from Cheryl, in an apartment by himself, spending much of his time going to sessions and seeing counselors.

Finally, one day, Cheryl called him: “I think you’re ready.” Jerry moved back in. They attended counseling together. He sticks to the rules he’s laid out, not taking so much as an aspirin or a Benadryl without the blessing of a doctor.

“I’m very proud of him,” Cheryl says. “He is very concerned, very attentive to his behaviors to stay on the straight and narrow, to stay sober. That has taken a strength … and a willingness to stay alive.”

There are still things Jerry’s working through. But eventually, he would like to get involved in service work that will allow him to do some mentoring.

“It’s not about the money at this point,” he says. “It’s about being able to pass on what I have been able to take advantage of, and to help other people — whether it’s just one or two, or 10, or 100, you know?

“I never thought for a minute in my lifetime that I would have been able to stop drinking. … To be where I am today, as far as my attitude towards alcohol, it’s not even in my mind. … I never thought I’d ever get to that stage, so it’s possible.”